AGAINST POWER

The Eyes #9

6/11/2018

AGAINST POWER

By Léa Bismuth

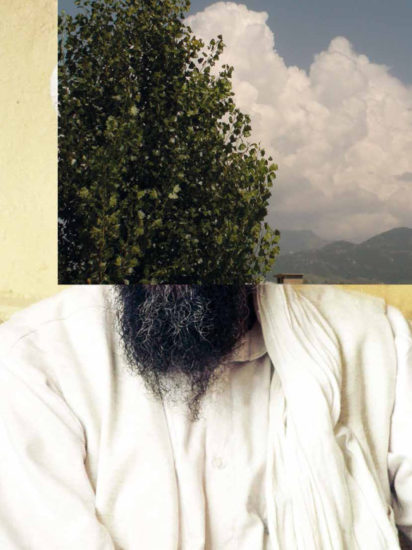

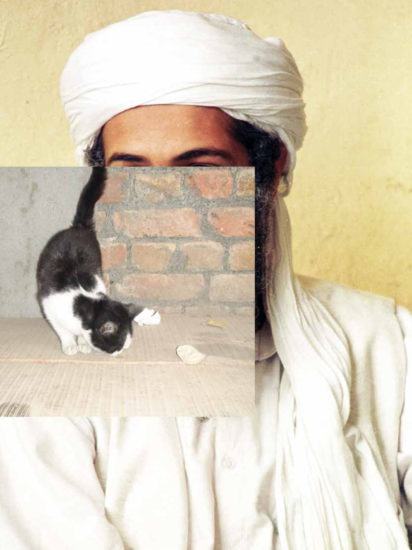

Without causing much of a stir, the CIA recently released on the internet the entire digital content found in the fortified complex of Abbottabad, the much-publicized hideaway of Osama bin Laden where he was killed by the US Army in 2011. David Fathi retrieved that content for misuse, in the way that power can be misused: he reconfigured the amateur photographs taken by bin Laden’s stooges into a laughable atlas of their rathertrivialinterests (cats,flowers,rainbows,badlyframedlandscapes),banal photographs that he then mounted on the face of the world’s most wanted terrorist, in a subversive distortion. This series is part of “Against Power”, his ongoing work in progress, divided into chapters, methods and units.

Power, in the political sense – in connection with techniques of governance and the application of power over – e directly raises issues of subordination and domination. Who asserts power over whom, for what purpose and with what means? Does it still mean anything today to claim to be against power? Perhaps. At least, David Fathi, a contemporary archaeologist of the Google era, takes hold of a raw material that, at times humorously, he uses as an instrument for world criticism. In his previous project featured at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2017, “The Last Road of the Immortal Woman”, he was already describing the strange case of Henrietta Lacks, an African- American woman who died of cancer in 1951 but whose cells would serve as case study for millions of modern scientific and medical experiments.

Halfway between documentary and science fiction investigation, Fathi ceaselessly evades codes. With “Against Power”, he keeps his eye open, gleans, searches and builds paradoxical knowledge, inventing his very own rules to organize and hierarchize the digital data. In fact, he engages in an undermining process, confronting the arcane of the internet, searching for signs that would allow him to dismiss the antics of dominant powers, geopolitical conflicts or fake strategic and interplanetary icons. For example, he also retrieves videos produced during missile tests in the planet’s skies, notably above North Korea, which he describes as phenomena of “choreographed propaganda”. The deterrent missiles are no longer visible, only contemplative traces of the clouds’ trails, atmospheric events conducive to meditation. And yet, this is about a blind war. Subverting the iconography of power, Fathi creates a tension in nomenclatures and categorizes absurd forms like the songs listened to by dictators or “tiny hands”, the typography created based on Donald Trump’s childhood handwriting, thus reducing the world’s “prominent figures” down to a cruel and inefficient little playground. This allows him to establish his programme of erosion, subversion, neutralization and deconstruction: “As a relative force between two actors, power thus can be rejected. Refusing to acknowledge power is already one step towards destroying it,” he writes.