Conversation with Józef Robakowski

Interview, The Eyes #7

15/11/2018

The Image above all

Interview of Józef Robakowski by Amaury Chardeau & Klaudia Podsiadlo

Illustration by Mélanie Roubineau

Born in 1939, Józef Robakowski is a major figure of the Polish “neo” avant-garde scene that emerged in the 1960s. Film director, photographer, teacher and collector, the artist relentlessly questions the limits of visual expression. As Poland prepares to celebrate the centenary of its pioneers, he discusses with The Eyes his artistic research spurred by the country’s political upheavals.

Which of your photographs speak of your origins?

Józef Robakowski: I can’t think of one single image, rather family photo albums. They were old, 19th-century richly adorned albums. My father put them together from photos he took of the family. He was a rich landlord from an aristocratic family, an officer in the Polish military, and lived with his wife in the countryside north of Warsaw. He was killed in the fighting against the Nazis in September 1939, shortly after my birth.

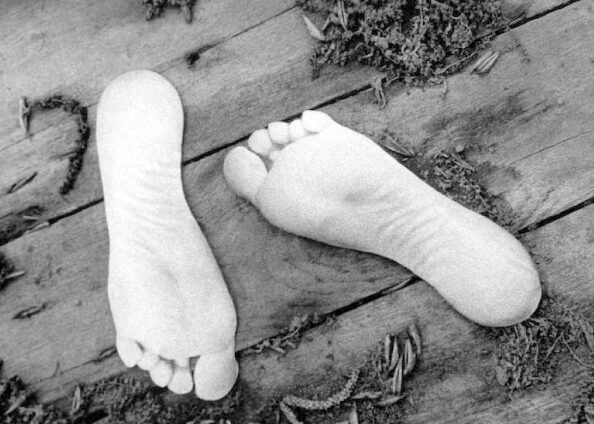

My mother raised my brother and me alone, but in 1944, after the Communist takeover, an agricultural reform imposed collectivization on large farms. It was a very violent period, with a great deal of looting. I was about four years old, and I can remember the Russian soldiers and local peasants coming to our farm and taking away our cattle, our farming tools… We were forced out of our farm, and we wandered for several years. Among the objects my mother was able to bring along was one such photo album. I inherited it from her, and it is very dear to me. Much later, as an artist, I used the album for an exhibition in Warsaw as a means to bring forth the memory of that aristocracy before the war, which had totally been erased from the official history.

A contemporary art museum recently asked me to make another such installation. A woman then contacted me, who happened to be the daughter of my wet nurse. She returned to me few objects that had been stolen from us, including another photo album, but whose images had all been ripped away.

Were you shaped by that?

Yes. I immediately understood that I could not support the Communist regime. For me, the history of Poland ended with the Second World War. This is what our Art History professors in Toruń told us. Most came from Vilnius, which was annexed by the Soviets. They advocated a status of art devoid of its materialistic function. As such, they protected us from Communist ideology. Our work as students was based on the conception of “art for the shake of art” when we founded the collective Zero-61. The purpose was to contest the pervasive ideology, to produce photographs without caring about the realities of the times or the materialistic philosophy imposed by Socialism. We did not have access to the official exhibition venues or to the galleries. We would clandestinely invest in these spaces and produce our catalogues ourselves to escape censorship. It was very “underground”.

What were the art movements that influenced you? Dada comes to mind…

Yes of course. In school in Toruń, we had access to an amazing library where we could look at all kinds of books about Surrealism, abstract art or Dada… We were exceptionally lucky, because in those days, no Western art was ever shown in the press, except maybe now and then for a reproduction of Cézanne or Pissarro… You need to remember that it was impossible to find a book about occidental art until 1958 in Poland.

Our models were the Polish artists from the early 20th century Witold Wojtkiewicz, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Stanisław Wyspiański… It had nothing to do with the prevailing tastes of the time.

After studying Art History, you joined the National Film School in Łódź, a highly respected institution considered one of the most important in Europe…

Yes, I had been making films for a few years. After failing admission the first time my photos were deemed too abstract – I was finally admitted to the school in 1966. My time there was determinant. It was a crossroads between East and West. The teaching staff included great Russians pedagogues and talented students like Roman Polański or Jerzy Skolimowski as well. These two had already produced their first masterworks, Polański with Two Men and a Wardrobe and Skolimowski with Identification Mark: None. It was the ideal place to reflect upon what contemporary art was about, a salutary respiration in Poland at the time!

How did you find your style?

I wanted to part from Socialist cinema, and also from the romanticism based on literature that impregnated Polish cinema at the time, like Kieślowskiorn Wajda. The school in Łódź had a wealth of films from before the war in its archives. There, I found unfeatured films by Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, the pioneer couple of experimental cinema who were working in the 1920s. And one day, in the storage of the Łódź Art Museum, I came across photomontages pro- duced by several photographers in the interwar period. It opened up new horizons.

I wanted to do different, even if this meant being alienated from Polish film directors’ circles. I wanted pure cinema, thus my manifest published in 1971 entitled “Pure Cinema Again”. The point was to return to the cinema principle of the 1920s, but keeping in mind the conscience that we had of our own times. To produce films that would be bare of any literary influence and that would focus rather on a plastic dimension, voluntarily abstract, both in sound and images. So we started to observe Łódź through the lens of our cameras, aiming to represent the city and its identity sometimes in slanted, even absurd ways.

Like for example in Market, the short film you made in 1970, which through a very long still frame, accelerated through editing, shows the movement of a crowd throughout the day at the market?

Exactly. The idea for this movie came to me on the occasion of regular trips to Moscow. I was then already familiar with the work of Dziga Vertov, Russian Constructivism and also Polish Constructivism. Suddenly, we were starting to increasingly look to the East, rather than to the West, for inspiration.

Afterwards, you often use the city and its residents as objects for your studies…

Yes; in 1973, for example, we made an installation for the Łódź Art Museum. It was called Action Workshop. Thanks to one of the professors at the school who also managed a TV station, we had access to professional material, notably an OB [outside broadcasting] van. So we set up three cameras: one in front of the museum, one in the workshop of a carpenter and one in the apartment of a family, and throughout the day we broadcasted life happening in the three locations to the museum. This was a pioneering undertaking, and also a technical achievement for the students. At the time, I think it was the only place where this could have happened.

And then there is From My Window, a project undertaken over the span of two decades between 1978 and 2000, filming the street from your apartment, resulting over time in a form of fresco of the collapse of Communism…

I was living in a neighbourhood of the city called “Manhattan”, which was quite ironic considering I was living in a tower that looked more like a housing project! I wanted to go beyond analytical cinema and shoot in the way of reportage, while injecting my own experience in it and a commenting voiceover. Initiated in 16 mm, the film was finished in video. In the end, it’s a diary of the city’s transformation from Communism to Capitalism. This is what I call my “personal cinema”, one that I continue to make today and that echoes to the evolutions of our country…

Actually, how do you consider the current political evolutions in Poland, and notably regarding culture?