Conversation with Ryuichi Kaneko

The Eyes #7

15/11/2018

Conversation with Ryuichi Kaneko

Interview by Marc Feustel

Illustration by Mélanie Roubineau

When did you first discover photography books?

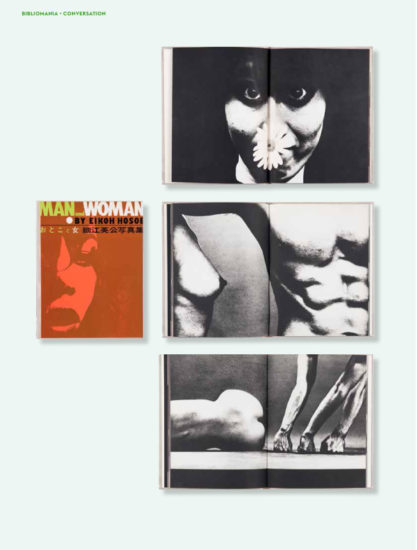

In 1967 – I was in my first year at Meiji University. I was part of the Zen-Nihon Gakusei Shashin Renmei students’ union [All Japan Students Photographers Association, or AJSPA]. At the time, there was a seminar organized by the photography critic Tatsuo Fukushima, during which he showed slides of several photobooks: William Klein’s Life is Good and Good for You in New York, Robert Frank’s The Americans, Eikoh Hosoe’s Man and Woman, Shōmei Tōmatsu’s Nagasaki 11:02 and Ed Van der Elsken’s Love on the Left Bank and Sweet Life. I discovered these books for the first time through this lecture.

What motivated you to begin collecting books?

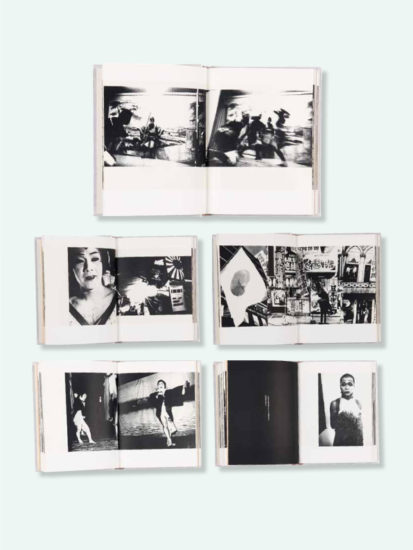

Seeing William Klein’s New York was my motivation. I was also very intrigued by Eikoh Hosoe. In 1968 there were quite a few second-hand bookshops in the Kanda area of Tokyo. Hosoe’s book Otoko to Onna [Man and Woman, 1961] was quite cheap, and many bookshops carried it. I was a student and didn’t have much money at the time, but 900 yen (ca 8 euros) I could afford. It was the first photobook that I found interesting enough to buy. The second book I bought was Daido Moriyama’s Nippon gekijō shashinchō [Japan: A Photo Theater, 1968]. I had seen his work serialized in the magazine Camera Mainichi, and I was also very interested in Shūji Terayama, who wrote the text for Moriyama’s book.

The third book was the original edition of Klein’s New York, the first foreign photobook that I bought. These three books made me feel that photobooks could be something special, different from photo magazines. I felt that a special world existed within these books. But photobooks were expensive and I couldn’t buy many. So I turned to the old photo magazines of the 1950s and 1960s, and studied the photographs in these magazines. The decision I made to start collecting came from one photobook. It was the Japanese version of Robert Frank’s The Lines of My Hand [Yugensha, 1972]. The publication of his new photobook was announced in a weekly journal of photography criticism, inviting readers to pre-buy the book for 7,200 yen (ca 62 euros). I had graduated from university and had started working at the temple, so I had a little money, but this book was quite expensive. But I really wanted to buy it, so I went to the post office and wired the money.

Almost 10,000 yen (ca 87 euros) for one book that I had not even seen… I started wondering why I had decided to do this. I then realized that it was something very important for me; it gave me joy. Once it was ready, the publisher, Kazuhiko Motomura, came to my home to deliver the book himself. I was later able to visit his house, where he showed me the photobooks that he owned. He told me about photobooks and bookshops. His taste in books was different from mine, and that helped me to understand my personal taste better.

My idea was to collect foreign and Japanese photobooks equally. Motomura was more interested in foreign photobooks. He was very strict when he selected books and didn’t buy many. In my case, if I was even a little interested by a book, I would buy it. That’s why I started buying a great range of books.

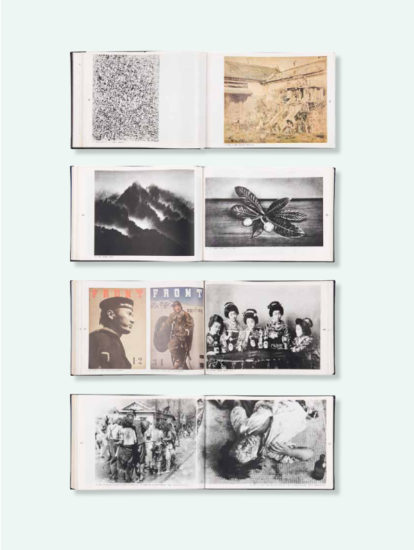

In 1971 Nihon Shashin Shi, 1840–1945 [A History of Japanese Photography 1840–1945] was published. It is a very thick book that includes many photographers and photographs, with very little text. When I first saw this book in 1973 or 1974, I realized that the history of photography inJapan was vast. I thought this book was wonderful, and it made me want to know more about the history of Japanese photography. I then became interested in pre-war photography magazines. The many public libraries in Tokyo didn’t have photography magazines or photobooks in their collections. But the used bookstores in Kanda all had them. They became my library. This library was even better than the public libraries because you could buy the books and take them home [laughs]. I bought all the old Japanese photography magazines. By 1976 I had quite a large collection, and had gained knowledge of Japanese photography through these magazines.

What was the role of the photobook for the student photography clubs of the 1960s? The books that they produced are very different to any standard idea of a photobook, both in terms of how they were made and their purpose.

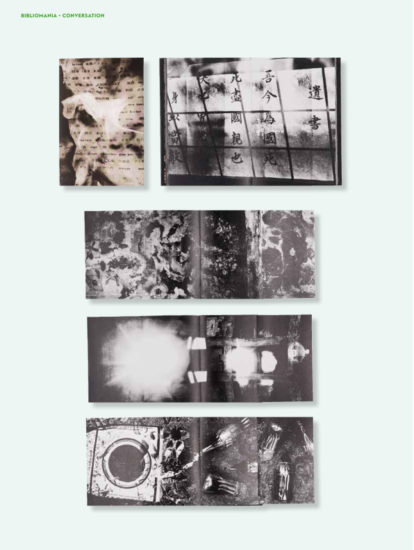

Tatsuo Fukushima had become involved as an organizer in AJSPA in 1965, and the organization changed drastically under his influence. The union was no longer just a circle: it had become a cultural movement. People started to question the act of taking photographs, and to explore the possibility of photography being created by a group. Within that context, the students’ union started to collect photographs from students and to sequence them for publication. Fukushima was heavily involved in this process. The small photobook Jōkyō 1965 (Conditions 1965, 1966) was published, followed by Ashibumi hikōki (Treadle Airplanes, 1966). AJSPA were not interested in the personal act of taking photo- graphs: they were thinking about creating a movement with photography.

Is it fair to say that these books were considered to be tools of activism? Were they designed to try to encourage action rather than to document?

Neither. The students were trying to do the same thing as profoundly artistic photography books like Tōmatsu’s Nagasaki 11:02 [1966], Kikuji Kawada’s Chizu [The Map, 1965] or Moriyama’s books. Nagasaki was seen as an artistic book, although these were undoubtedly photographs thatweretakentoprotestagainsttheatomicbomb. It was a very specific social act in that sense, but also a cultural act that was aimed at the heart of the field of photography. The students’ motivation was to create this kind of cultural movement, not a political or artistic movement. Of course, there were photobooks that were explicitly designed to be tools of activism, such as Kon chijō ni wareware no kuni wa nai/Kogai kyampēn shashinshū [No Country on Earth for Us/Pollution Campaign, 1970], which focused on pollution. This book also had a message inviting readers to become involved with the antipollution movement. The act of seeing – of looking at – a photograph is to recognize that there is something there, something visible that has been captured in the photograph, while also causing an emotion to arise in us. A photograph does not just contain information: it also moves our emotions – it is an experience. This type of book was meant to create a specific emotion and experience that would lead to action. Conditions 1965 was different.

Provoke was published in this context. What was the reaction in the photography world?

Very few people bought the magazine Provoke at the time. I think this was because it was difficult to find anywhere to buy copies of it. I did eventually buy it and I was quite excited by it, both by the images and the text. But its impact was very limited since so few people saw it.

The magazine was sent to established photography magazines like Camera Mainichi or Asahi Camera, as well as to photography critics. But of course it wasn’t sent out to the general public, and it was difficult to buy. So there was a big difference in the reaction among the general public and the photography establishment.

At the time, we weren’t as interested in the ideas behind Provoke, but rather the expressionistic photographic style that it was based on. In my view, its influence was not so much on the existing photography establishment, but rather on the younger photographers of that generation.

You have frequently referred to photography magazines. Do you feel that they played as fundamental a role in the development of photography in the 1960s and 1970s?

Yes, absolutely. Without these magazines, Japanese photobooks and the forms of expression which emerged from them would not be anywhere near as dynamic. You can look all over the world – there is nothing quite like the Japanese photography magazines of that time. What was most unique about these magazines was the idea of a series on a theme. They would explore a specific theme over the course of a year and devote 10 pages to that theme in every monthly issue. If you were to publish portfolios in one of these magazines over the course of one year, you would have 120 pages’ worth of images, which is equivalent to a photobook. This went on from the 1950s until the early 1980s. So in a sense, photography magazines had become a base from which to create photobooks. For a photographer, presenting their work in these magazines was a significant achievement. Publishing a photobook was then considered to be a further step up. In that sense, the culture of magazines nurtured that of photobooks.

In recent years, there has been a major shift in photographic history in the West. Photobooks have been recognized as having made a major contribution to the development of photography in the 20th century. Is that also the case in Japan?