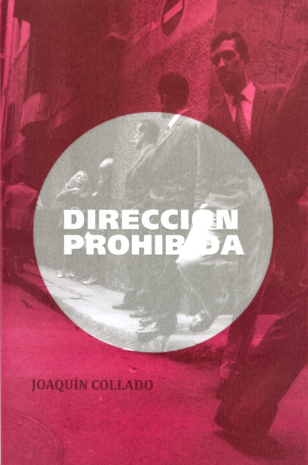

Direccion Prohibida

Joachim Collado

Direccion Prohibida

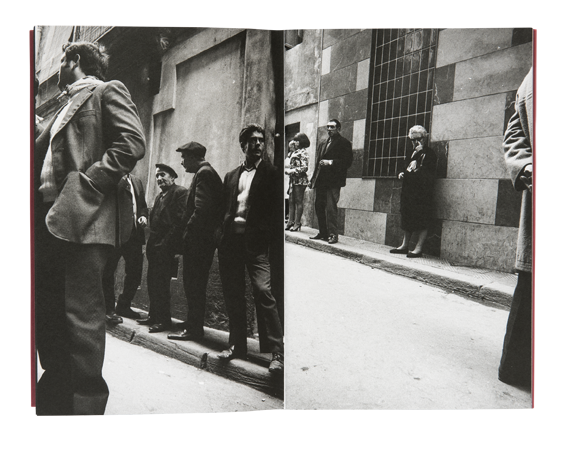

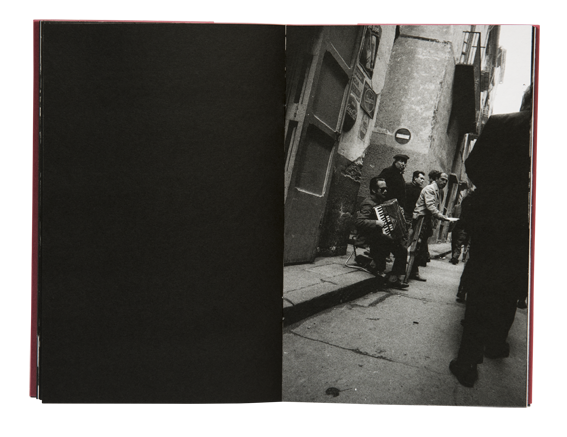

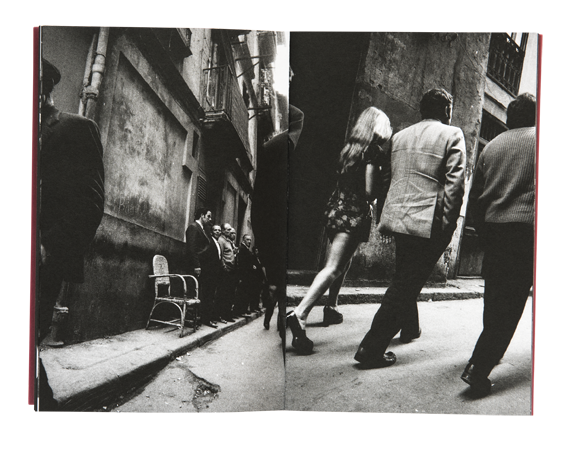

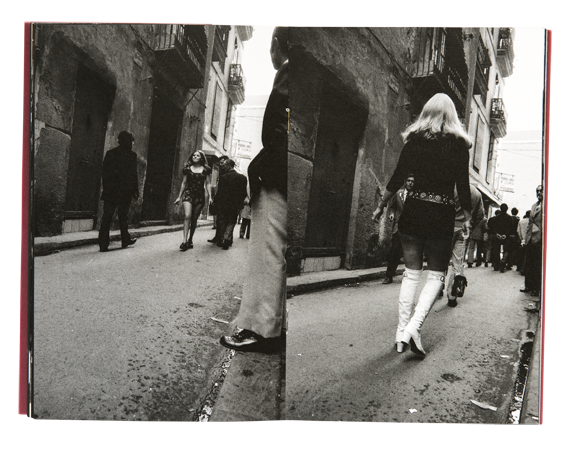

Sunny Sunday. Half past eleven in the morning. Valencia’s Barrio Chino, in the heart of the city. Pedestrians occupy the street. It is a very busy and dark place, where prostitutes and mackerels, shopkeepers, travelling musicians and craftsmen live together. A place of agitation and movement where curious people and snoopers of all kinds come to rinse their eyes and satisfy their sexual needs.

It is a day of celebration, Father’s Day, and men crowd the sidewalks, following with a lustful gaze the voluptuous bodies that are exhibited under the arcades. Joaquín Collado came to this place to bear witness with his camera to this lecherous and voracious atmosphere. He knows well that at that hour the four old and dirty streets that make up the perverse centre of the city will be full of people waiting for the arrival of the spring of the flesh.

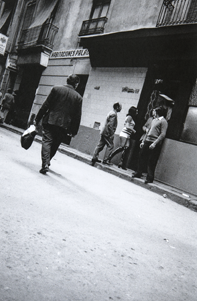

He walks around discreetly, pretending to be a tourist, hiding the Nikon FTN he’s wearing so that people don’t notice he’s come to steal a piece of their secret lives. As he moves around, he coughs in order to hide the discreet detonations of his camera, and he tries not to miss any of the details of this human spectacle.

Aged 42, Collado is an amateur photographer who went to the forbidden zone with very clear intentions. He is unaware that other photographers have done the same in Paris (Brassaï) or Barcelona (Joan Colom).

It’s not a big deal. His look is original. In 1972, Collado saw the city as an authentic stroller, an “asphalt walker” who explores stories to be told with his camera. The city of Valencia is bogged down in the lethargy of the end. of a dictatorship that lasts too long and represses the country’s cultural development. Photography lived during the 1940s and 1950s on an aesthetic pictorialism, on the exaltation of beauty. However, new photographers emerged who, in the decade of the 1960s, constituted a young generation of creators who broke with this trend.

No aesthetic unity among these photographers, but the same vitality in attitude. All of them were influenced by Italian Neo-Realism, and are part of a network of photographic associations that regularly receive international photography magazines and directories, and which link their members to what is happening in other countries: Cartier Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Eugène Smith, Robert Franck, William Klein, Irving Penn, or even one-off exhibitions such as The Family of Man, already imply a broadening of perspectives and a new orientation towards other ways of seeing.

From his position as a self-taught photographer, Joaquín Collado is part of this renovating movement, whose gaze is tinged with anthropological and humanistic connotations. His work can be understood as a visual essay on the city and its inhabitants, an exercise in collective memory and in meeting others.