With the Eyes of Sartre

The Eyes #5

14/11/2018

With the Eyes of Sartre

Text by Hans-Michael Koetzle

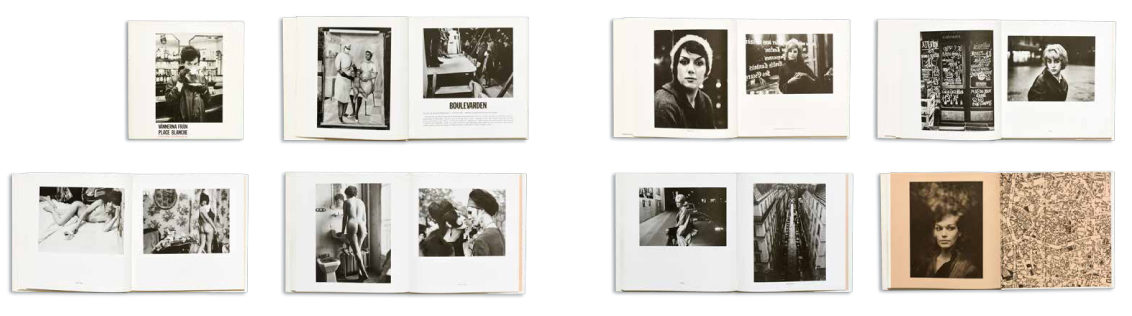

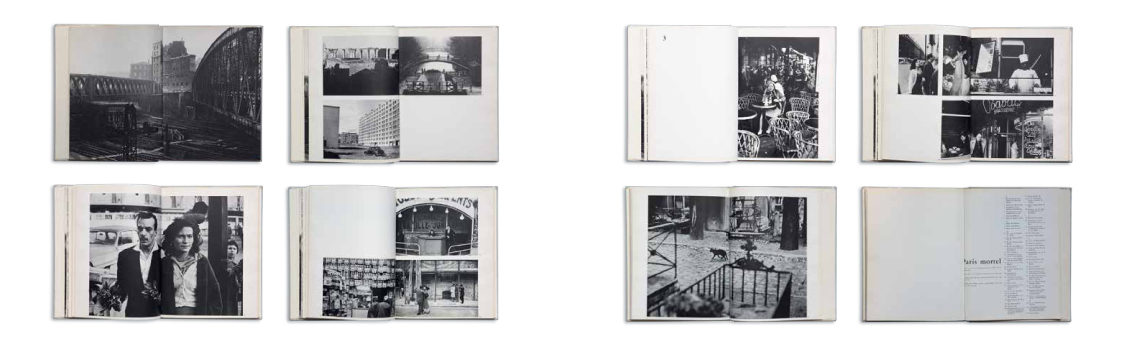

Between Existentialism and Situationism, three major books show Paris in the 1950s and the 1960s.

There are no solid statistics. And yet, it is relatively safe to say that Paris is the world’s most photographed city. This technology was launched in Paris in 1839. It then seemed obvious to point the camera and the lens to whatever was at arm’s length: the immediate environ- ment, the River Seine or the boulevards, the Louvre or Notre-Dame. Already, the 19th century had bequeathed us countless magnificent views of Paris using the most distinctive photographic techniques, from daguerreotypes to prints on salted paper, albumen photographs or gelatin silver prints. After the unique print came the portfolio, essentially intended for tourists; and as it became possible to print photographs in the 1890s, the book with photographic illustrations emerged. Along with the postcard, these illustrated books largely shaped our fantasy vision of the capital city. There are two kinds. On the one hand we have the representative photobook aimed at travellers, conveying a majestic representation of the capital through classical views. On the other, we have the author book, an illustrated volume conceived by an artist photographer for whom form and content are equally important: and Paris became an excuse for a novel approach to the world – as evidenced by the sensation caused by Brassaï in 1932 with his collection of photographs, Paris de Nuit [Paris by Night]. The books by Moï Ver (Paris), Ilya Ehrenburg (Moi Parizh [My Paris]) and André Kertész (Day of Paris) also deserve a mention. The artists were all immi- grants, all from Eastern Europe. Each one sketched a personal and innovative image of the city, both formally and aesthetically.