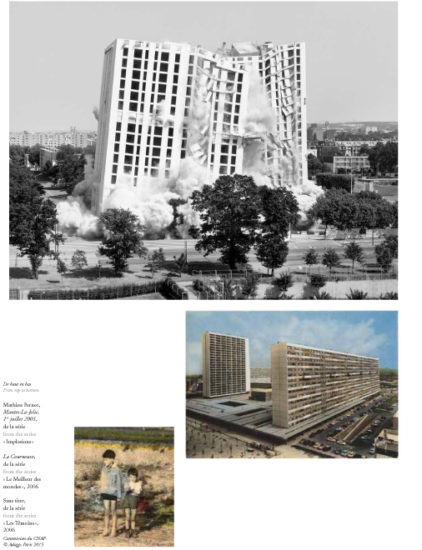

Scenography of illusion

The Eyes #5

15/11/2018

Scenography of illusion

Text by Dominique Baqué

Our focus on Paris gives us an opportunity to question contemporary French photography. Today, it seems at its best when it deals with the notions of the document and the alleged veracity of what the image repre- sents. Dominique Bacqué leads us through a reflexive, perhaps typically French trend.