Conversation with Paul Wombell

Interview, The Eyes #1

14/11/2018

Conversation avec Paul Wombell

Interview by Amaury Chardeau

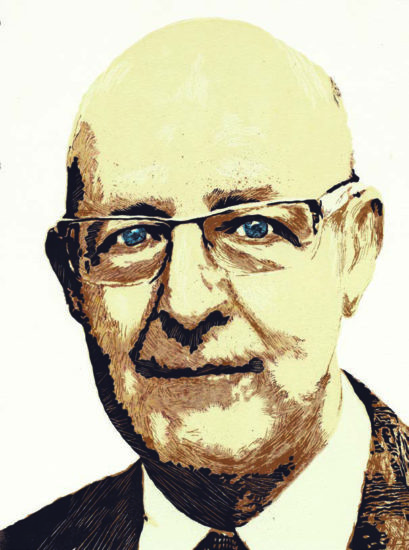

Illustration by Fabrice Pellé

As an independent curator and writer on photography, Paul Wombell is a key figure of photography in the UK, and one of the most dynamic thinkers on the future of this medium.

Tell me about your background…

I was born in the north of England in a town called Doncaster in Yorkshire. It was a very traditional working class background. My father was a glass cutter and my mother was a housewife and then worked in a factory canteen. I was the first member of my family to access to higher education. Most of the kids I grew up with went to work in the mining industry.

When I was still at school, I delivered newspapers to make some pocket. It gave me access to magazines I had never seen before like The Sunday Times Magazine. Later, when I started working full-time, I found a quirky newsagent that sold international and political magazines. I started buying Rolling Stone, Creative Camera, a political magazine called Oz and most of all Paris Match: I couldn’t read French but the photographs were so extraordinary that they took me to another world. In the early 1970s, I came to London and soon afterwards started watching experimental films at the London Film-Makers’ Co-Op. Then in 1974 I was accepted at St Martin’s School of Art: this was a major transformation in my life. I remember the first year there, it was pure excitement. I just wanted to know more!

After my studies in St Martin’s, I went back to Yorkshire where I got involved in running the board of trustees of a photographic gallery called Untitled Gallery, now called the Site Gallery. I eventually became the chair of the board. The position of director came up in York in Impressions Gallery, which was the second photographic gallery to open in the UK, in 1972. I applied and I got the job.

You now live in London where the interest in photography seems to have increased these last years: The Photographers’ Gallery extended its exhibition room, new galleries opened… even the Tate Modern has now a specialized curator in photography!

Yes, that is amazing! That was not the case in the 1980’s or in the 1990’s. When I left Impressions Gallery to join The Photographers’ Gallery in 1994, the Tate was buying photography prints, but you rarely saw them on show! At that time, I am not even sure that private art galleries were selling prints.

There were two important events: first there was the creation of Channel 4, which had a commitment to engage in contemporary culture across the UK. When I was in Impressions Gallery, they used to come quite regularly to feature some of the exhibitions we had mounted. And the second one was the launch of a new newspaper called The Independent. They had a commitment to photography, and as a small gallery in York, we were getting coverage in the national newspaper. That started to change the landscape of cultural activity in the UK.

How do you explain that photography was ignored for so long?

At that time, it was all about a culture that was more interested in literature and not in the visual arts. In many aspects, even today, the UK still seems like an old country. You would never go to the Tate to see a photography show, they rarely included photography in any show. The interest was just not there, but there was a fundamental cultural shift during the late 1980s and 1990s in London. I remember very early on when I went to The Photographers’ Gallery and said “we want to display this piece”, and the curators at the time said “no, it’s fine art, we display documentary here, not Andreas Gursky”. One of the first shows I organized was about the City and we borrowed Paris Montparnasse by Gursky from the Tate. It was a big picture and I remember very clearly the day when it came in, I felt we were really changing things! We worked in a very complex way, with established cultural institutions, with department stores. We were trying to find ways to make photography live not only in galleries: for instance, in 2001, we worked with Channel 4 to do an amazing project on the way people defined the new century. We had three simultaneous exhibitions in Liverpool, Edinburgh and London with a range of TV programme. We were open to anything that could embody photography the medium of photography could be about: fine art, press photography, anonymous or studio photography…

You’ve always been interested in trying to extend the field of photographic studies… Last September, you were invited as a guest curator in Montreal where you organized an exhibition about drones and automated images… Tell me about your views on this issue: is the document “dead” for you?

No, for me it is more fundamental: I don’t think photography documents anything. There is no connection between the document and photography. The photographic print is a compression of light and time in miniature two- dimensional form in which we can recognize a person or a location. But it is much broader and wilder than any form of documentation. The document suggests an end of time and no room for imagination. The photographic image is more like a dream than a fact; it can suggest the future and other complex ideas about the world.

In 1991 I curated a show called Photo Video. The purpose was to show how the nature of the photographic medium was changing. It may have been one of the first exhibitions about digitization of photography. I have always been interested in how technology reformulates, not just the image, but what it might mean to be human. This is the underlining theme in Montreal. I find it fascinating to think about all the instruments that humans have created. The history of the camera goes back 3,000 years: its development relates to the invention of the wheel, of the lens, of the clock, etc. All these different elements can be found within the camera.

My hope in Montreal was to change the way we look at the camera, to create a sense of marvel, to make us think about its history, what it can do and what it might do in the future. What are the implications of the automation of image-making. If you think of Google Street or Google Earth, this is imagery made without humans, and I am very fascinated by this kind of contradiction between how humans “remake” themselves, and the implications of that in terms of the future.

Today, a lot of trading on the stock exchange is done by mathematical calculations, and a small but growing part of journalism is done by computers that can generate stories for newspapers!

Recently, at the University of Cambridge I think, they opened a department to study the relationship between humans and technology. We live in a world full of technology and machinery, we can’t live without it. But where does the equilibrium of power lie, and what could make it shift? When you think that a camera can be put inside your body to observe a disease, or sent to Mars or other inaccessible locations, we realise that human vision can only extend itself thanks to technology!

Recently, you were asked by four French photographers (Cédric Delsaux, Jérôme Brézillon, Frédéric Delangle and Patrick Messina) to supervise their newly created photographic mission on lanscapes which should be released in 2014. Why did you agree to get involved in the project? And tell us about “France(s) territoire liquide” (France Liquid Territory).