MY SHADOW’S REFLECTION

The Eyes #9

6/11/2018

MY SHADOW’S REFLECTION

By Marc Feustel

Prison photography could be described as an exercise in making visible that which has been specifically designed to be beyond our gaze. An artist who chooses to work in this environment has to contend with an array of obstructions, the foremost of which, in Edmund Clark’s view, is that “people effectively disappear when they become prisoners”.

My Shadow’s Reflection is an attempt to disrupt this process. Through an exhibition at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham and this publication, Clark has articulated a deliberate, multi-faceted approach to punch holes in the barrier separating the “inside” from the “outside” and thereby open channels between “our” world and “theirs”.

The project is the result of Clark’s three-year artist residency at HMP Grendon, Europe’s only entirely therapeutic prison. All Grendon’s inmates requested to be sent there, and made a full-time commitment to intensive group therapy to analyse and understand why they are incarcerated.

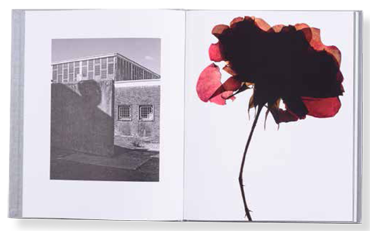

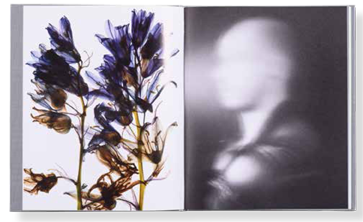

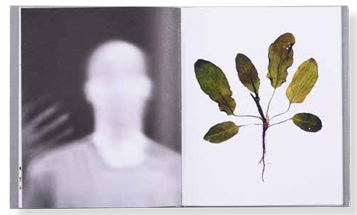

Although Clark was forbidden from making images that reveal the prisoners’ identities, portraits are the book’s primary ingredient. Using a pinhole camera, he took long- exposure portraits of each participant as they responded to questions about themselves, their crimes, the prison and their therapy. These blurry, black-and-white images are not clear enough to result in a likeness of their subjects, but they still give a phantomatic impression of each individual inmate.

These portraits are interwoven with a handful of formal black-and-white photographs of the prison’s relatively unremarkable 1960s brick architecture. The book’s other main visual ingredient is altogether more surprising: throughout the project, Clark collected flowers and leaves from the prison grounds, which he then pressed. Printed on a different paper stock to the other images, these colour photographs reveal each plant in sharp detail, down to the veins of the leaves or the stamens of the flowers, in direct contrast to the murky blur of the pinhole portraits. Such images would generally be found in a botanical scrapbook, but in this context they act as invitations to consider the unfavourable conditions in which these plants were able to grow, and suggest a form of beauty in this resilience.

The final piece of the book is the four-page insert of text at its centre. Printed on a lurid green paper (the colour of the prison-issue sheets that the inmates sleep in), the text is made up of the inmates’ reactions to Clark’s pinhole portraits of them. The remarks are unattributed and shuffled together, each one separated by a simple square glyph that recalls the closed form of a prison cell. They veer from horror or rejection to amazement – the book’s title comes from one of the prisoners who likened his portrait to “an X-ray of my shadow’s reflection with a suntan!” As with many of Clark’s books, the role of the text is crucial, as it pushes the project beyond a process of observation and depiction into a form of reflexive dialogue, providing a window into the therapeutic process at Grendon and questioning the nature and purpose of incarceration.